Bono’s Next Chapter: A New Story Unfolds

Near the conclusion of our initial afternoon together, Bono casually mentioned the renowned Irish poet W.B. Yeats’ nearby burial site. It was early April, and the U2 lead vocalist was guiding me towards my vehicle along the driveway of his French Riviera vacation home. The Mediterranean Sea stretched before us, a breathtaking panorama of endless blue. His expansive property unfolded—several houses, a couple of pools—a haven of seclusion despite its proximity to Monaco and Cannes. Bono is not the first Irishman to exchange his homeland’s damp climate for the sunny Côte d’Azur, but he may be doing it with more style than his predecessors.

He shares this idyllic retreat with his bandmate, the Edge. In the early 1990s, while vacationing there with the rest of the band, they noticed the property and decided to explore further. However, Larry Mullen and Adam Clayton, the band’s drummer and bassist, declined to even exit their car; maintaining such a property would be excessively demanding, they asserted. But the band’s frontman and guitarist couldn’t resist making the purchase. U2 had recently concluded a decade of remarkable success, transforming from a promising post-punk band to a global stadium act, selling over 70 million albums. In short, they could afford the extravagance.

Maintaining the property has, in fact, demanded considerable effort. They have expanded the buildings to accommodate their expanding families. That day, one building was undergoing renovations, and one pool was drained—preparations for the upcoming summer season. However, this picturesque getaway has offered Bono and his band more than it has taken away.

A few days later, seated in one of the living rooms, Bono remarked, “This place saved our musical lives.” The surroundings were both impressive and relaxed. Two large gray couches, expansive windows overlooking the sea, a piano in a corner, and a large fireplace behind us provided a warm, welcoming ambiance. Yet, despite the years spent there, he still maintained his signature rock-star style. While his neighbors favored linen and pastel-colored vacation attire, he remained true to his Dublin roots, dressed in black jeans, a black V-neck T-shirt, and an army-green jacket.

The years leading up to acquiring the summer residence had been thrilling but also utterly exhausting. Bono described the process of becoming one of the world’s biggest bands as akin to “pushing a rock uphill.” The constant pressure had affected them all. U2 had transitioned into Serious Musical Artists, but they hadn’t yet mastered the art of enjoying their success. “We were slow to the party,” he admitted.

And perhaps that’s what saved their music. Subsequent albums, including 2000’s *All That You Can’t Leave Behind* and 2004’s *How to Dismantle an Atomic Bomb*, were highly successful. (We will let individual listeners judge 1997’s *Pop*, a somewhat divisive album in the group’s discography; personally, I enjoyed it). However, extended conversations with Bono revealed that he had found something else in the South of France; “It’s the antidote to one of my personalities,” he explained. This personality, that of a relentless artist, had pursued the largest stages worldwide, coveted awards, and explored new frontiers of music and visual expression for over four decades.

While acknowledging that complete anonymity was impossible, Bono noted, “It wouldn’t be fair to say we could live an anonymous life here, but the French are so respectful. You could almost forget that you weren’t anonymous.” After thirteen years of intense focus on their career, Bono finally learned to relax. He indulged in leisurely meals, late nights, family time, and social gatherings. “House parties, dance parties, our friends,” he recalled fondly of those early years. Bono thrived, discovering a sense of lightness and ease he hadn’t felt in a long time.

Reflecting back, he acknowledged that he may have taken things too far. “I was experiencing the pure joy of adolescence backward—in my thirties instead of my teens,” he recalled. “There was a moment where I had to ask myself, ‘Where is this self-love and where’s this self-indulgence?’ ” However, he expressed gratitude for the experience.

His family visits regularly, primarily during the summer months. School, work, and individual pursuits keep everyone busy. Bono enjoys these occasions when the house is filled with family. “If you have a place like this, lots of people should use it,” he stated simply. Bono and his wife, Ali, have four children, aged between thirty-five and twenty-three. The Edge has five, and some grandchildren are now part of the growing family. When asked what the Edge’s grandchildren call him, he was momentarily surprised. “Bono,” he replied after a pause, adding, “You have to remember, Edge’s mother used to call him Edge.”

However, he often spends considerable time alone in the French home. “Working like a dog, living like a shih tzu,” he quipped.

This week was no exception, though he had invited me to discuss his latest film, *Bono: Stories of Surrender*. Filmed during his solo stage show, which ran from late 2022 to early 2023, it’s a candid adaptation of his memoir, released in 2022. The film premiered at the Cannes Film Festival before its May 30 release on Apple TV+. Some might dismiss it as a nostalgia-driven money grab by an aging rock star, but this is a misunderstanding of the man and his current life stage.

The past few years have been a period of healing and self-reflection for Bono, who turned sixty-five this spring. He overcame a serious health scare (which he had downplayed publicly) and gained a more balanced perspective on life’s simple pleasures. He confronted childhood demons that have fueled his career, and reassessed his role in the philanthropic endeavors that have consumed much of his energy for decades. He has engaged in deep introspection and emerged transformed—improved.

Despite the introspection, Bono remains driven. The relentless energy that has propelled him and his band for nearly fifty years persists. He is energized, similar to his early days in the South of France. U2 is currently in the studio recording new songs—potentially their first album of new music in almost a decade—and his enthusiasm is evident. Bono clearly has more stories to share, and he believes the world needs to hear them.

His one-man show’s transformation into a multimedia project wasn’t initially planned. The show’s dates were already scheduled when Apple Studios approached him with a filming proposal. However, the frontman and the tech giant quickly expanded their vision, resulting in two versions: a standard screen version and an immersive experience for the Vision Pro, which includes Bono’s original artwork. “It became more of an undertaking,” Bono admitted. Director Andrew Dominik joined later, making it a rigorous process.

As one-fourth of U2—a band known for its collaborative approach—Bono has frequently navigated creative differences. But Dominik challenged him unexpectedly, urging Bono to confront the emotional scars left by his mother’s death and his complex relationship with his father, in ways his memoir had not fully explored. The results are not merely artistic; they have profoundly affected his life, liberating him from years of pent-up anger and resentment.

Bono described his relationship with Dominik as collaborative, except for Dominik’s initial desire to create a documentary about the show. His bandmate, the Edge, helped explain why this wouldn’t work: “It was Edge, actually, who told Andrew, ‘You find Bono onstage. You’re not going to find him backstage.’ ”

Bono is multifaceted—a charismatic rock star, activist, and compelling performer. Dominik refused anything that felt staged. During rehearsals for a particularly intense scene, Bono recalled standing on a table (representing a hospital bed) portraying both himself and his dying father, Bob Hewson. He poured his emotions into the performance, but Dominik wasn’t satisfied.

“Nah, mate, you’re acting!” Dominik exclaimed.

“There’s no one there!” Bono retorted. “What am I gonna do?”

Dominik’s response: “Don’t act.”

When asked if it worked, Bono simply replied, “Well, you’ve seen it.”

Regarding his feelings about the film’s release, he confessed, “I feel a bit of nausea… And I really am fed up with the protagonist.”

The origin story of U2 is now legendary. In 1976, fourteen-year-old Larry Mullen Jr. posted a flyer at his Dublin high school, Mount Temple, seeking musicians to form a band. Paul Hewson, David Evans, and Adam Clayton responded. Mullen was a skilled drummer, Evans (the Edge) showed early guitar talent, Clayton had an edgy demeanor, and Hewson craved community.

Hewson, who later adopted the name Bono, was still grieving his mother’s death two years earlier. “This guy was really, really, really alone,” recalled Gavin Friday, a childhood friend who lived near Bono. Their friendships deepened because of their shared experiences. Bono’s father, Bob, was forty-eight when Iris died and developed a social life. Bono’s older brother, Norman, led an independent life. Bono was left at home with little to do; each man was isolated. After Iris’s passing, they never spoke her name again.

Bono’s charisma helped him cope. Friday recalled Bono’s routine of visiting him for fish and chips on Fridays (meat wasn’t consumed on Fridays in Ireland) and his use of his charming personality to secure meals from other families. Friday laughed recalling this, emphasizing Bono’s resilience: “Man, what a survivor,” he added, “How hard it was for this little boy to be alone in this house—no mother, no father, no brother, no money.”

Bono had a difficult relationship with his father, Bob. He never felt seen or appreciated and was often subjected to harsh remarks from his father, fueling a desire to achieve such significant success that his father would be forced to acknowledge his accomplishments.

This proved partially successful. The band has sold 175 million records and won twenty-two Grammys. Bono fronted a stadium act for over four decades and owned homes in Dublin, France, New York, and Los Angeles. Yet, the success wasn’t complete. Friday shared, “I have a memory of being at the Joshua Tree show in New York and I was standing beside Bob Hewson. And Joshua Tree was going off, and the crowd was just euphoric. And I touched him and said, ‘You must be so proud of your son.’ And he said, ‘Yeah, I am, but I’m not going to tell that fucker.’ ”

When Bob died in 2001, Bono still harbored resentment. He struggled to process his emotions, but after his wife suggested he blamed Bob for his mother’s death, he gained a new understanding. He realized his father’s struggles as well. A year later, near Easter, Bono visited a nearby chapel and sought forgiveness from his father. “I was expecting the apology,” Bono recalled, “but I think the conversation had been the wrong way around.”

Healing began. Writing his memoir helped, but the stage show proved the most therapeutic experience. Reciting his father’s cutting remarks to an audience and eliciting laughter surprised him. “I realized it was his sense of humor,” he said. “My whole life it came across as only cutting, but I realized how very funny it was.”

He also gained self-awareness. “That I had been a little humorless,” he said. “I should have laughed more rather than be so hurt by it.” He reflected on the importance of laughter, questioning if he had been humorless himself.

He also considered that his strong desire for social justice was partially inherited from his father. “I started to realize that all of those arguments that we used to have at the kitchen table, he was always on the side of social justice,” he said. “He owns that part of me.”

Bono wishes he had seen his father more clearly during his lifetime. His current peace is tinged with sadness. “I began to really like him, as well as love him,” he said, describing the change in his feelings during the performances. Eventually, “I even began to miss him.”

Let’s be clear: liking Bono isn’t guaranteed. He’s aware of this. A member of one of rock ‘n’ roll’s most provocative bands, U2, he’s always divided audiences, starting with the band’s third album, *War*, which reflected their youth amidst political violence. “Sunday Bloody Sunday,” about the 1972 killings of civilian protesters in Derry, Northern Ireland, became a signature song, making the album a major success. It also foreshadowed their future work.

During their early albums (*Boy* and *October*), Bono, the Edge, and Larry Mullen Jr. grappled with religious beliefs. Their association with a fundamentalist Christian church, Shalom, conflicted with their lifestyle. As their fame grew, so did their pastor’s disapproval. They realized their music needed to have meaning if they were to continue. Many criticize U2 for never pretending otherwise; they haven’t striven for coolness, and their success is deliberate. Sincere, sometimes earnest or even sanctimonious, they have worked hard and been open about it. They declared rock ‘n’ roll could change the world and acted on it, writing about political conflicts, international relations, and justice. They challenged authority from their stage.

This has created a complex relationship with their home country. Growing up during the Troubles, U2 championed peace, advocating for non-violent methods and demanding an end to international funding for violence in Ireland. “For certain people of a certain generation, we carry a lot of baggage,” he said. “And for some people, we’re helping them with their luggage.”

Controversies haven’t helped. Accusations of tax avoidance have surfaced, though Bono has maintained their actions were legal. There was also the 2014 iTunes gifting incident, where users received a free copy of *Songs of Innocence* without their consent. Bono took full responsibility.

Jimmy Iovine, a record executive and Apple Music executive, praised Bono’s honesty. He met U2 in the 1980s and pursued them to Ireland to collaborate. “He’s one of the most honest people that you could possibly work with. No matter what happens, Bono doesn’t blame anybody. He takes full responsibility for everything in his life.”

Bono’s repeated mention of the mixed reactions to U2 (“We were loved and loathed… it really was both”) suggests he may find amusement in the band’s detractors. He views it as part of their work. “They say sometimes, you know, ‘You better have your armor on. You’re about to walk out and get killed.’ Isn’t that what you’re supposed to do?”

In 2016, Bono underwent open-heart surgery at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York City to repair an aortic aneurysm. It was a condition he had lived with, but it posed a life-threatening risk. Recovery was difficult, and the Joshua Tree album’s 30th-anniversary tour loomed. He recalled struggling with breathing after the surgery. Decades of singing in stadiums had given him exceptional lung capacity, but he suddenly felt a loss of control. “It terrified me,” he said. “I’d never been so terrified.”

His team suggested canceling shows, but Bono refused. For the first time, he accepted his limitations. He continued the tour but remained stationary during performances. The results surprised him. “The singing improved,” he admitted. “I started to realize I had just been shouting for a living,” he said.

His condition improved, and in his seventh decade, he feels he’s creating with new vibrancy. “I had better find some really great songs for it,” he said. He collaborates with the Edge, and “There’s nothing else that he or I want to do that comes close to it.”

While his surgery wasn’t kept secret, he avoided discussing it in interviews. Now, he expresses gratitude for the experience. Health scares often prioritize life’s essentials, prompting appreciation for one’s life and path. For Bono, it led to reflection on his life’s various stages: the 2017 Joshua Tree anniversary tour, his memoir, the 2023 album *Songs of Surrender*, the Achtung Baby revival—all culminating in *Bono: Stories of Surrender*. “I don’t believe in destiny, but it happened in the right order,” he says. “You wouldn’t want to stay there too long, but you do have to acknowledge where you came from, at a certain point.”

His family encouraged him to slow down. They urged him to focus on daily life. What constitutes daily life? “Genuinely,” he recalled, “they said, ‘Things like watching TV.’ ”

Someone suggested the Chef’s Table docuseries. Bono was initially skeptical, but his Netflix binge began. He enjoyed the series, noting its value system and inspiring figures. His daughter, Eve, introduced him to other shows, including *Fleabag* and *The Kardashians*. He slowed down, said no more often, and reevaluated his involvement in (RED) and ONE, eventually stepping down from the board.

Bono founded ONE in 2004 and (RED) in 2006. They are as significant to him as his music. He stepped down in late 2023 to promote a new generation of activists. “I’m the wrong sex, wrong age, wrong color, wrong ethnicity, and I’m not African,” he said. He misses the work.

He acknowledged his “messiah complex,” common among rock stars. However, he also considered the current political climate. “The most unbelievable carnage imaginable is happening to our work at (RED) and ONE,” he said, referring to cuts to global relief efforts. “These are the brightest, best people, who’ve given their lives trying to serve the poorest, most vulnerable communities, and they’ve just been thrown in the dumpster.”

Bono has collaborated with both Republican and Democratic administrations. This has drawn criticism from the left, especially his partnership with George W. Bush during the Iraq war. However, he remains unfazed, citing the AIDS relief program as a significant accomplishment. He identifies as a “radical centrist.” “And I am sure that that sounds absurd, but I am also sure that is how we get through the future. What’s being served up on the far left and on the far right is not where we need to be.”

The Trump administration initially challenged him, prompting a shift in his worldview. Before 2016, he often reflected on a Martin Luther King Jr. quote about justice. He no longer believes it’s solely a matter of time; “We have to bend it,” he said. “Through sheer force of will.”

Yet, he admits, “I don’t know how to proceed.”

For forty years, Bono has championed globalization. He has invested his reputation and resources in the belief that a more interconnected world benefits everyone. He witnessed its impact on Ireland’s development and its contributions to Africa. A decade ago, he felt progress was being made. Now, he observes a resurgence of nationalism. “I’ve been very angry,” he said. “But you don’t have the luxury.” Too much is at stake.

He’s particularly concerned about the United States. “The United States has been a promised land to a lot of people, but it looks like it’s about to break that promise,” he said. “I can understand people coming to a place where they say, ‘I don’t see why the United States has to pay for aid, drugs, or anything else in places far away where there is no vote.’ I think that position is dumb. I think it makes a lot of geopolitical troubles for you down the road, but I can understand it.”

He finds the disregard for life-support systems alarming. “The delight that was taken in the destruction of life-support systems—pulling them out of the wall—that’s the clue to the true nature of this. Evil walks amongst us, but it is rarely this obvious.”

Bono clings to a few sources of hope: a potential unity in Europe, the belief that informed Americans will make sound choices, and the conviction that freedom is more enjoyable. “You see these people—they don’t look like they’re having any fun. You need that anarchic spirit to change the world. Pot-smoking, opinionated, fun, adventurous people like Steve Jobs. Einstein sticking his tongue out. You don’t get that in autocracy. We’ve got to bring freedom with us, everywhere we go.”

He referenced a Jeff Bridges interview discussing the search for harmony. Bono understood the sentiment, connecting it to the natural world. This led to discussions about the Franciscan idea of God’s presence in creation and Pope Francis’s encyclical, Laudato si’, which advocates for environmental protection. The connections were apparent, always returning to the initial point. “It’s a beautiful idea, when you start to see a walk in the park as a kind of cathedral,” he said.

Bono’s self-awareness remains despite his tendency towards grand ideas. He’s grounded, often using humor. “Of course,” he added, “it’s also important to note that a tree can also just be a tree. It doesn’t have to be a lesson in Latin.”

He credits his wife of forty-two years, Ali, for her wisdom. And he recalled advice from Chrissie Hynde: “I remember her saying, ‘Hey, let’s not die stupid,’ ” he said. “ ‘Not in a swimming pool, choking on your own vomit. Come on, man. You know what’s really great? Living a long life. That would be great, wouldn’t it?’ ”

Bono’s face lights up when discussing his children. He dotes on them, even as adults. “If I was shaped by trying to get my father’s attention,” he said, “those kids have been somewhat shaped by trying to get their father’s attention off of them.”

They returned to Dublin to raise their children, sending them to a free, non-denominational school reminiscent of Bono’s own. They tried an alternative approach with their younger children in New York, but they returned to Ireland. They valued Dublin’s lack of deference to their fame and its culture that doesn’t equate wealth with interest. As Gavin Friday noted, “The Irish are pretty good at bashing their own.”

When the family is together, Bono observes. Eve and John are comedians, Jordan is forceful, and Elijah, a rock singer, is drawn to authenticity. “He is uninterested in cool,” Bono said of his son, “but I think he might bump into it anyway.”

Ali provides stability for the family. “I need an appointment to see her,” Bono joked. He admires her calmness. Bono met Ali the same week he met U2, expressing continued awe at his good fortune.

He’s overjoyed to see his children’s dreams come true. However, he also acknowledges the time spent away on tours and in Africa. His children pose difficult questions. “Do you know where you were on my eighth birthday?” He gives Ali credit for their upbringing but notes their shared desire to make a difference. “All of them gather around a prayer, and the prayer is to be useful,” he says.

I pointed out the contrast between his ambition, driven by a desire to prove his father wrong, and his children’s success in a loving, privileged environment. This raises a question: is relentless drive inherent?

Bono paused before responding, “You don’t want what I have,” he said. “I’m really grateful for the fire in my belly and whatever kind of pugilist it made me—to try and put a finer word on a man who can just throw a bad punch in a pub. But I would say all of our kids have a deep desire to do something with their lives…” He didn’t finish, but he returned to the point later. His children balance engagement and detachment, acknowledging privilege while also pursuing their passions. They pray to be useful and enjoy entertainment.

But Bono hasn’t found an “off” switch.

“Did I play you that song the last time we spoke? It was in my head—‘Freedom Is a Feeling.’ ”

Bono didn’t play the new song then, and he didn’t play it this time, on Zoom. He began to sing a snippet, “Free-dom,” he hummed, “is a feeeEEling.”

This reflects his current creative journey. The band is working on new music, and he wants the music to reflect his commitment to freedom. This idealistic talk may draw criticism, but U2 has a way of delivering emotional music that resonates deeply with listeners.

He has hinted at a new album for years. (“Where is it?” I asked. “Madison, you are such a buzzkill,” he retorted.) There’s reason to believe that fans will hear the album soon.

Larry Mullen has faced back problems, and Bono has processed his personal experiences. “We were a little broken,” he admitted. “There was a period of reflection where we had to figure out, do we have anything to offer?” The answer, he’s happy to say, is yes.

This means Bono is ready to return to his role as hype man. “We’ve got a band unlike any other—good or bad—but unlike any other,” he said. He highlighted the unique talents of each band member.

The new material sounds impressive to Bono. “Everyone in the band seems desperate for it,” he said. “It’s like their lives depend on it.” He paused. “And, as I tell them, they do.”

They’re working with Brian Eno again. Bono seeks to return to the essentials, referencing a line from *All That You Can’t Leave Behind*: “‘I’m not afraid of anything in this world / There’s nothing you can throw at me that I haven’t already heard.’ ” This reflects Bono’s perspective on the male experience. “That’s really on my mind at the moment,” he admitted.

Bono prefers performing live to recording. He judges a successful release by a single criterion: “If it provides us with a reason to leave home.” Tour. “You want to have some very good reasons to leave home.”

“I hope they’re going to still be there for us,” he said of their audience. “We’ve pushed them to their elastic limit over the years. And now it’s a long time that we’ve been away. But I still think that we can create a soundtrack for people who want to take on the world.”

U2 has closed many shows with “40.” It’s a reflection of a question Bono constantly asks himself: “How long, how long, how long / How long to sing this song?”

It seems, a little while longer.

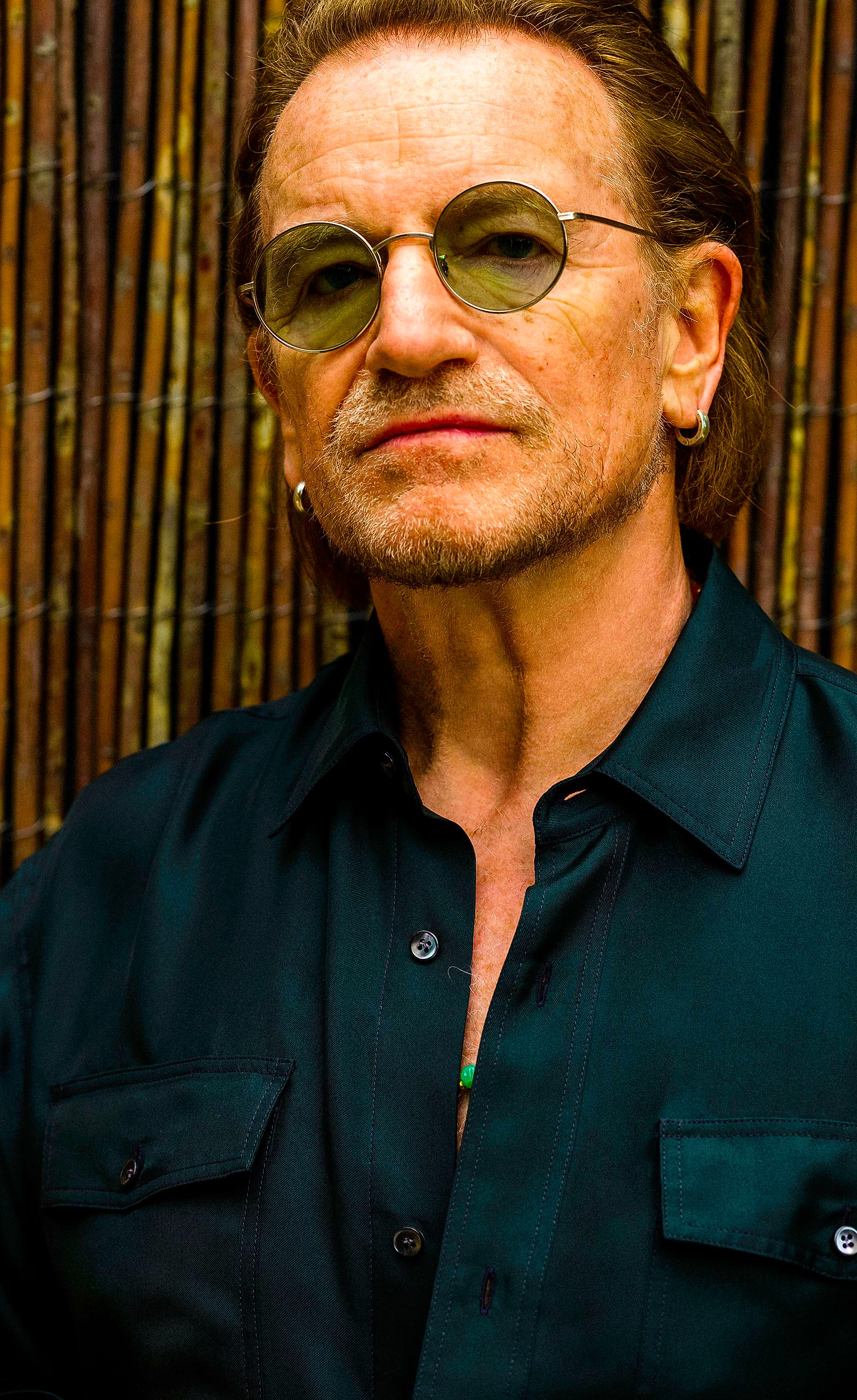

In the opening photo: Jacket by Dries Van Noten. Sunglasses and jewelry, Bono’s own.

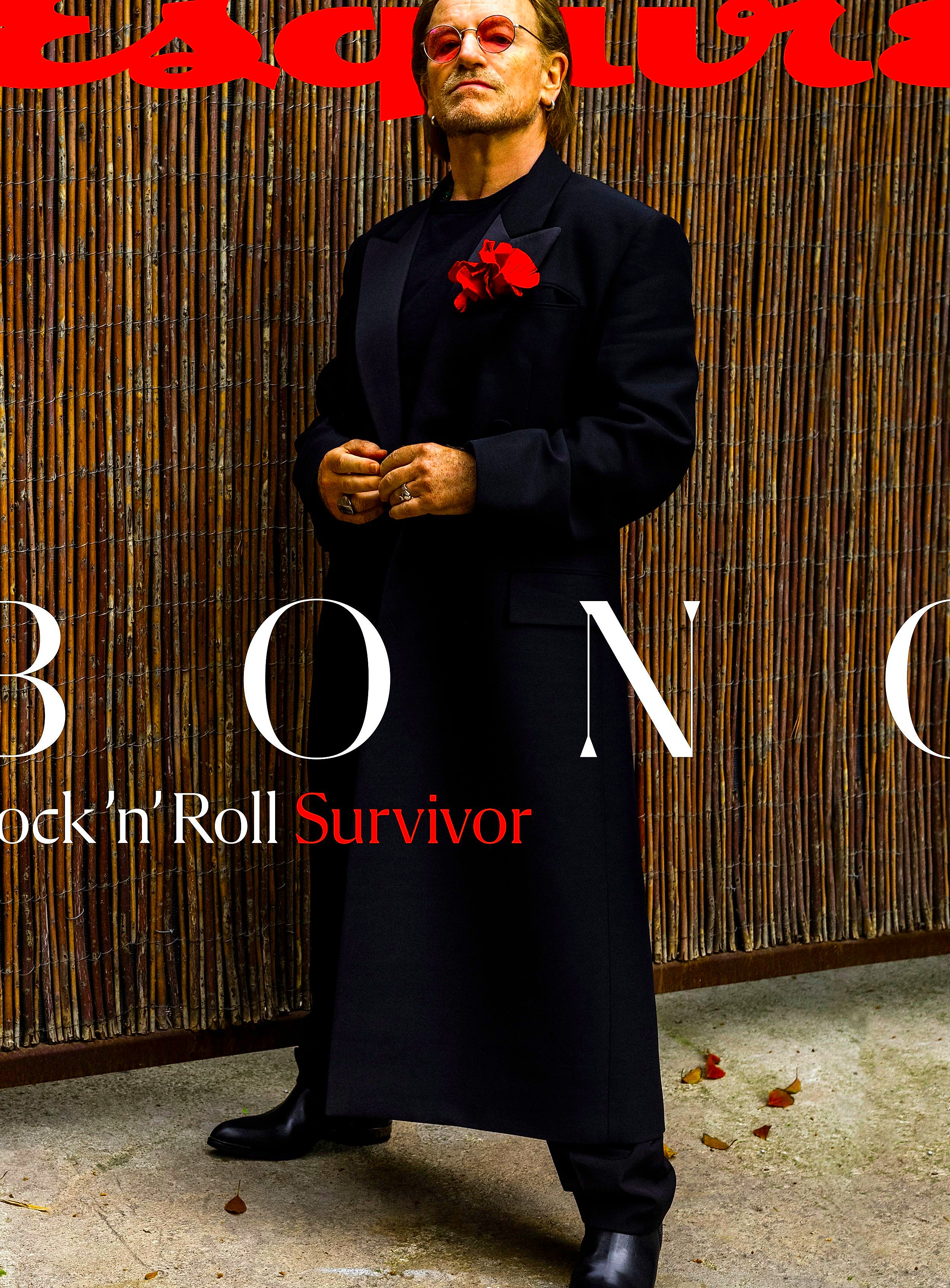

In the cover image: Coat, trousers, and pin by Ferragamo; T-shirt by Dries Van Noten; sunglasses, shoes and jewelry, Bono’s own.