A New Narrative from Bono

Near the conclusion of our initial afternoon together, Bono mentioned W. B. Yeats’s nearby burial site, referencing the renowned Irish poet. It was early April, and the U2 vocalist guided me up the driveway of his French Riviera vacation home to my car. The Mediterranean Sea stretched before us, a breathtaking expanse of blue. His expansive estate included several houses and pools, providing an idyllic retreat despite its proximity to Monaco and Cannes. Bono is not the first Irishman to swap the damp climate of his homeland for the sunny Côte d’Azur, but he may be doing it with exceptional flair.

Bono shares this property with his bandmate, the Edge. In the early 1990s, while vacationing with the rest of the band, they noticed the property and decided to take a closer look. However, Larry Mullen and Adam Clayton, the drummer and bassist, declined to even exit the vehicle; they found the prospect of owning and maintaining such a large property overwhelming. However, the lead singer and guitarist couldn’t resist the temptation to purchase it. U2 had recently completed a decade of extraordinary success, transforming from a promising post-punk band into a stadium-filling rock act, selling over 70 million albums in the process. This success meant they easily could afford such a luxury.

Maintaining the property has required significant effort. Over time, additional buildings have been constructed to accommodate their growing families. During my visit, one building was under construction and a pool was drained—preparations for the summer season. Nevertheless, this idyllic retreat has been incredibly beneficial to Bono and his band.

Days later, while sitting in one of the living rooms, Bono shared that this property saved their musical careers. The environment was beautiful but relaxed; two large gray couches, floor-to-ceiling windows overlooking the ocean, a piano, and a large fireplace created a welcoming ambiance. Despite the relaxed setting, Bono’s attire remained distinctly his own. While neighbors donned linen and pastel colors, he was attired in black jeans, a black V-neck shirt, and an army green jacket – the quintessential Dublin rock star look.

The years leading up to purchasing their summer home were exhilarating but exhausting. Bono described the process of becoming a world-renowned band as akin to “pushing a rock uphill.” The relentless pressure had taken its toll; the band evolved into “Serious Musical Artists,” yet they hadn’t mastered the art of enjoying their success. He admitted they were slow to adapt to their newfound fame.

Their acquisition of the summer home possibly helped preserve their music. Subsequently, they produced exceptional albums: 2000’s “All That You Can’t Leave Behind” and 2004’s “How to Dismantle an Atomic Bomb.” (We will leave the assessment of 1997’s “Pop,” a polarizing release in their discography, to the readers’ discretion.) However, extended conversations with Bono revealed that the South of France provided him something more profound: “It’s the antidote to one of my personalities,” he explained, referring to his relentless pursuit of global musical success, awards, and artistic innovation.

Bono acknowledged that complete anonymity was impossible, but the French were respectful, affording them a degree of privacy. After thirteen years of intense focus on their careers, Bono finally learned to relax. He embraced leisurely lunches, late nights, quality time with his family, and socializing. He thrived, finding a lightness he hadn’t experienced before.

Looking back, he believed he might have overdone it, experiencing the exuberance of adolescence far later than most. He reflected on the balance between self-love and self-indulgence. Yet, he expressed gratitude for the experience. His family still visits, primarily in summer. School, work, and their own careers keep everyone busy. Bono enjoys having them all together, creating a vibrant atmosphere in the home. He values shared experiences in this special place.

However, he also spends considerable time alone, working diligently. This week was no exception; he invited me to discuss his film, “Bono: Stories of Surrender.” Filmed during his one-man stage show in 2022-2023, it’s a vulnerable adaptation of his 2022 memoir and premiered at Cannes before its release on Apple TV+ and Vision Pro. Despite some cynicism about a nostalgia-driven project, this film is a significant reflection of his life journey.

The past several years have been a period of recovery and introspection for Bono, who turned sixty-five this spring. He overcame a serious health crisis (which he downplayed publicly), gained a balanced perspective, confronted past traumas, and reevaluated his philanthropic work. He underwent a period of intense self-reflection and emerged transformed.

Despite this introspection, Bono isn’t one to remain idle. The driving force that has propelled him and his band for nearly five decades is still present. Similar to his early days in the South of France, he is feeling invigorated. U2 is currently recording new material—their first album of new music in almost a decade—and his enthusiasm is evident. Bono, clearly, has more stories to tell, and he believes the world needs to hear them.

He hadn’t initially planned for his one-man show to become a multimedia project. Apple Studios approached him to film the show after the dates were already set. However, the collaboration quickly evolved into two versions: one for the screen, primarily showcasing the live performance, and an immersive experience for Vision Pro, including illustrations he created himself. Director Andrew Dominik joined the project, leading to a demanding and intensive production schedule.

As one-fourth of U2—a band known for its collaborative approach—Bono has spent much of his life navigating creative differences. However, Dominik challenged him in unexpected ways, prompting him to confront the emotional scars from his mother’s death and his complex relationship with his father. The film’s impact extended beyond the project itself; it liberated him from years of pent-up anger and resentment.

Their only disagreement, Bono recalled, was Dominik’s initial intention to create a documentary about the show. His bandmate, the Edge, clarified the distinction between Bono’s onstage and backstage personas, influencing the film’s direction. Bono is a multifaceted figure—a charismatic performer, an activist, a campaigner. Dominik ensured the film avoided any sense of performance or theatricality.

During rehearsals, Bono recounted portraying himself and his father, Bob Hewson, during his father’s final moments. He was intensely committed to the scene, but Dominik pushed him further, urging authenticity over acting. The final product is compelling and honest.

When asked about his feelings prior to the film’s release, Bono admitted to feeling nauseous and weary of the protagonist. The origin story of U2 has become legendary. In 1976, fourteen-year-old Larry Mullen Jr. posted a flyer at his high school, seeking musicians to form a band. Paul Hewson, David Evans, and Adam Clayton responded to the call.

Hewson, who would later become known as Bono, was grappling with the loss of his mother two years earlier. His father, Bob, had also withdrawn into himself following his wife’s death. Bono, lacking a strong support system, felt profoundly alone. The family avoided mentioning Iris’s name after her passing.

Bono’s charm and resilience helped him navigate those challenging years. A friend recalled Bono’s resourceful ways of obtaining meals from neighbors, highlighting his ability to survive despite difficult circumstances. Bono struggled with his father, feeling neglected and wounded by his father’s sharp remarks. This fueled his ambition—not just to escape Dublin but to achieve extraordinary success that even his father couldn’t ignore.

In many respects, Bono succeeded. His band has sold 175 million records and won twenty-two Grammys. He has homes in multiple cities. However, his relationship with his father remained strained. Even at the height of U2’s success, his father remained guarded in expressing his pride. Bono’s anger towards his father persisted until his death in 2001.

After his wife suggested that his anger stemmed from blaming his father for his mother’s death, Bono experienced a breakthrough. He realized his father might have been struggling as well. A year later, Bono sought forgiveness from his father at a nearby chapel. The process of reconciliation and healing began.

Writing his memoir helped, but the stage show proved to be the most therapeutic. Performing his father’s cutting remarks before an audience and eliciting laughter surprised him. He realized his father possessed a dry wit, and he regretted his own lack of humor and emotional resilience in the past.

He also realized that his dedication to social justice might be partly inherited from his father, who held similar views. He now recognizes his father’s influence in shaping his activism. He deeply regrets that he didn’t have a closer relationship with his parents while they were alive.

Bono’s polarizing public image is well known. Since U2’s third album, “War,” which explored the impact of political violence, he has divided audiences. “Sunday Bloody Sunday,” about the 1972 Derry shootings, became a defining song for the band, catapulting their album to number one in the UK and shaping their career. During their early years, Bono and his bandmates struggled with their religious faith and the conflicts between their beliefs and rock and roll lifestyle.

They faced criticism for their earnest approach, which some found sanctimonious, and their unwavering commitment to meaningful music. They tackled political issues, international relations, and justice in their music, leading to a complex relationship with their homeland. Growing up during the Troubles, they campaigned for peace and against violence. Some controversies, such as accusations of tax avoidance and the controversial iTunes album giveaway, haven’t helped their image.

A record executive who worked with U2 praised Bono’s honesty and willingness to take responsibility for his actions. Bono readily acknowledges the mixed reactions to the band: both loved and loathed. He sees this duality as inherent to their career. In 2016, Bono underwent open-heart surgery to repair an aortic aneurysm, a condition he had lived with for years. Recovery was difficult, and the Joshua Tree anniversary tour loomed.

He faced post-operative breathing difficulties, a challenge given his exceptional lung capacity from years of performing. Despite initial fears, he chose to continue the tour, adapting his performance by standing still. Surprisingly, he discovered his singing improved, realizing he had been shouting rather than singing.

His health scare profoundly impacted his priorities. He embraced a slower pace of life, including watching television. He also reevaluated his involvement in his charitable organizations, recognizing that promoting a new generation of activists was essential. He stepped down from the shared board of ONE and (RED) in late 2023, acknowledging that he was no longer the ideal representative.

He admits to having a messianic complex, which he sees as a common trait among rock stars. However, he also acknowledges the devastating impact of political decisions on his philanthropic work, specifically the Trump administration’s cuts to global relief efforts. He does not see himself as liberal, but as a radical centrist. He believes that global cooperation is essential, but the rise of nationalism is deeply troubling to him.

He is concerned about the U.S.’s role in global affairs, but believes that America has the potential to be a better global partner. He is disturbed by the disregard for humanitarian aid and the casual destruction of vital programs that support vulnerable communities. He clings to the hope of a united Europe, believing that Americans, given the facts, will make the right choices.

He also believes that freedom is essential and that an anarchic spirit is needed to effect change. He draws inspiration from figures like Steve Jobs and Einstein. He finds comfort in his family life, especially his wife, Ali, whom he describes as wise. He is grateful for the warm, affectionate home he provided for his children in Dublin.

He acknowledges that his relentless ambition stems from a desire to prove his father wrong, while his children have grown up with love and privilege. He reflects on the idea that his relentless drive is simply an intrinsic part of his personality. His children, he notes, have a healthy ability to both engage with and disengage from the demands of life.

But the “off” switch has always eluded Bono. He mentions a new U2 song, “Freedom Is a Feeling,” and begins to sing it. It embodies his current creative pursuit, and the band is actively recording new music. Bono wants to embody freedom, not just sing about it.

U2’s drummer has been struggling with back pain, and Bono has been processing his personal journey. They questioned whether they still had something to offer, but ultimately decided they did. Bono is excited about the new material, saying the band is driven by a sense of urgency. They are collaborating with Brian Eno again, returning to a more essential sound.

Bono is a live performer, not a studio musician. His criteria for a successful album is simply: a reason to go on tour. He hopes their audience will remain loyal, despite their extended hiatus. They aim to create a powerful soundtrack for those who seek to change the world. U2 frequently ends its shows with “40,” a song that contemplates the question of how long to continue their work. Bono is now ready to continue his journey.

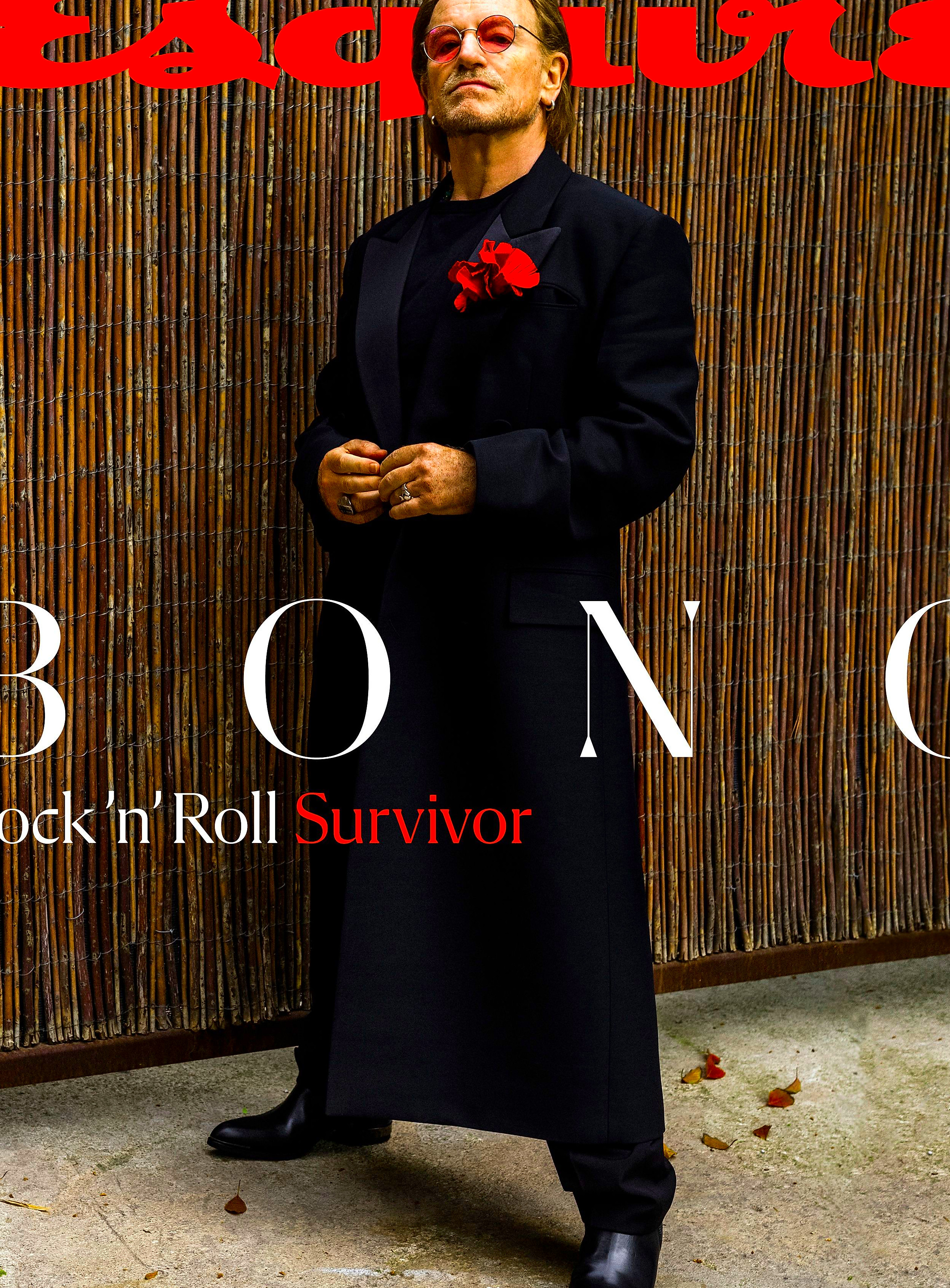

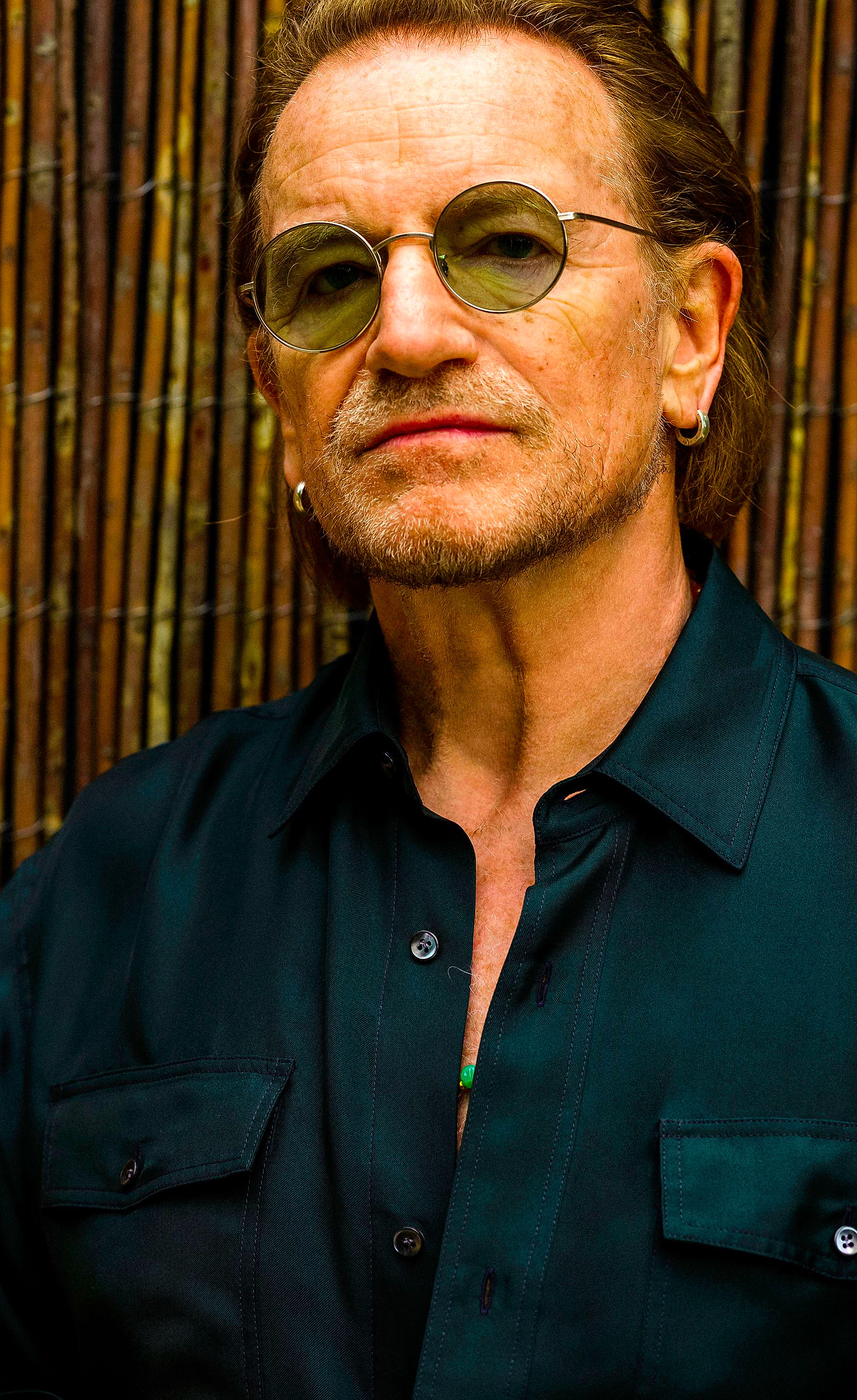

Opening photo: Jacket by Dries Van Noten. Sunglasses and jewelry, Bono’s own.

Cover image: Coat, trousers, and pin by Ferragamo; T-shirt by Dries Van Noten; sunglasses, shoes and jewelry, Bono’s own.